Using time to make better collective decisions

A simple explanation of our 'bond voting' mechanism

I don’t think the most interesting thing about blockchain technology is cryptocurrency. The most interesting thing is the new design space that blockchains open up for human coordination.

That design space is deficient in a lot of ways - at least compared to the real world. For example, establishing fixed identities on a blockchain is challenging, and linking on-chain activities to real-world actions can be complicated.

So any governance arrangement that relies on human reputation or requires enforcing contracts on identifiable people (like, for example, mortgages) is notoriously difficult to implement on on-chain.

On the other hand, blockchains are an very powerful machine for making impenetrably credible commitments.

Once you commit to some action (transfer, sell, really any contract call) with your private key, it is done, and done forever. Only massive coordinated action among a global community to roll back or fork the whole blockchain can reverse it. You could say that irreversibility is good or bad, but it is definitely new.

That’s why we have called blockchains a new institutional technology. And new institutions allow us to build new mechanisms for human governance.

Last year Vijay Mohan, Peyman Khezr and I published a paper in Management Science developing a new mechanism of our own: bond voting.

It is a very cool idea. And (we think) it is a very important and useful idea for communities wanting to experiment with better voting systems to get better governance. But that paper was written entirely for academics, with lots of formulas and math and stuff, so I thought I should explain it more straightforwardly here.

The basic idea

In most blockchain ecosystems, voters use their tokens to vote, and their voting power is weighted by the number of tokens they hold. This is basically like corporate voting which uses share ownership to weight votes. But token voting is more fun, because tokens.

Bond voting introduces another element to determine voting power: time.

Rather than simply voting with their tokens, participants must lock them up for a set period. The longer they lock those tokens up, the more voting power they receive. The basic idea is that the more a voter cares about an issue, the longer they’re willing to forego alternative uses of the token (like selling it).

Bond voting works well with blockchains because we use them to credibly lock tokens up, and once they’re locked, they’re locked.1

Three problems with voting

Bond voting solves three specific problems with voting for human governance.

The first is the (now) well-known problem that most voting systems don’t allow us to identify how intense a voter’s preferences are (preference intensity).

Imagine a group voting on what to cook. First, for dinner, they have to choose between pizza and pasta. Second, for dessert, they choose between cake and ice cream.

Most voting systems will simply ask a binary question - that is, which of these alternatives do you prefer? Pizza or pasta? Cake or ice cream?

But there’s a lot of information that this approach discards. One voter might be mostly indifferent to the choice between pizza and pasta. But they might really, really hate cake, and really, really prefer ice cream. That’s important information if we want to make an optimal social choice.

So the ideal voting system captures not just preferences, but how intense those preferences are. This was the intuition behind quadratic voting, where voters can buy (increasingly expensive) extra voting power when they really care about an issue.2

The second problem is plutocracy. In token voting - like shareholder voting - the more tokens you have, the more voting power you have. It’s a simple linear relationship. This relationship is much complained about but it is actually pretty good! All else being equal, the more at stake you have, the more incentivized you are to make good decisions.

But the linear relationship between ownership and decision-making is not an unalloyed good. A token holder with a smaller amount of stake might be more incentivized to make better decisions when their tokens represent a larger share of their personal wealth. So we want token holdings to matter but we also want other mechanisms to get information from highly incentivized group members into the decision-making process.

Finally, we want any mechanism we decision to be sybil resistant. Whatever mechanisms we introduce to deal with preference intensity and plutocracy need to make sure that voters can’t game the system by pretending to be more than one person, or by multiple voters pretending to be one person.

Sybil resistance is not usually a problem (other than voter fraud) in real voting systems, which are tied to real world identities, but is a big problem in blockchain ecosystems, which are not.

How bond voting works

At its heart bond voting is pretty simple.

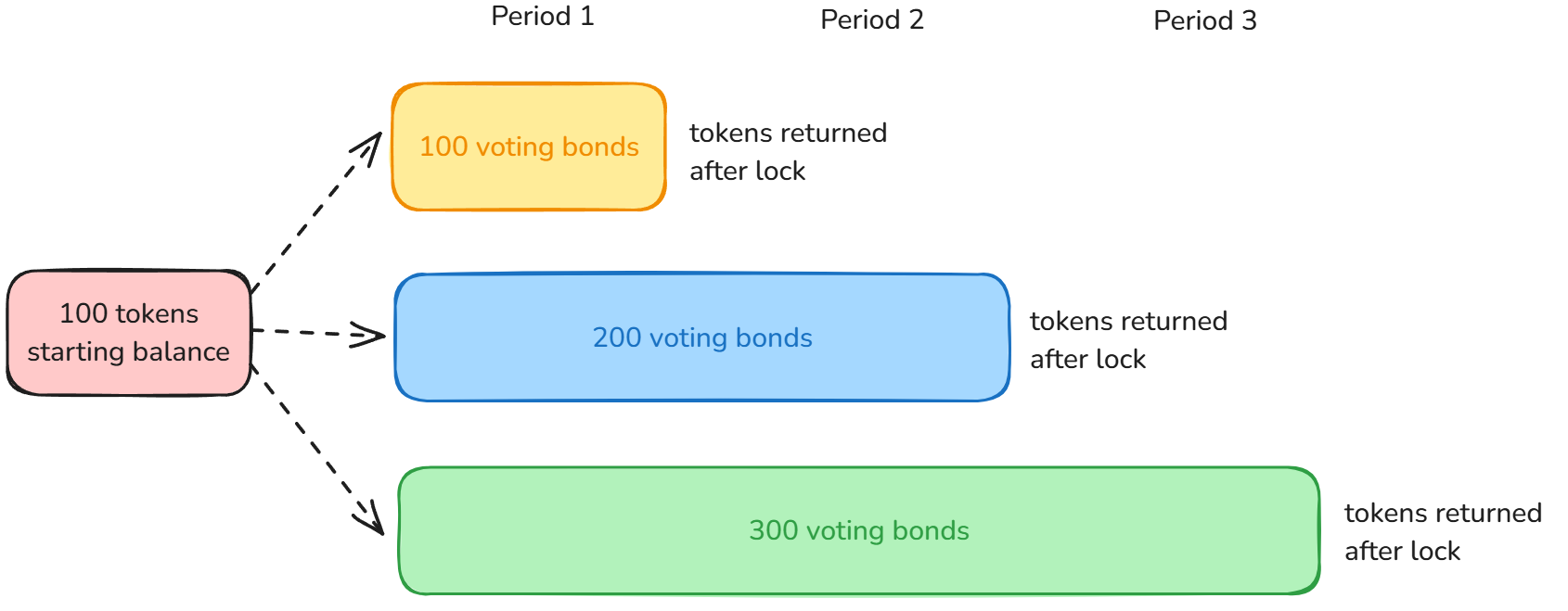

Instead of voting with their tokens directly, voters acquire voting bonds by locking up their tokens for a variable amount of time. The longer they choose to lock them up, the cheaper the price of those bonds will be. This means they can ‘buy’ more voting power per token.

They use those voting bonds to vote.

After the bonds expire, they get their tokens back.

For instance, suppose that a voter starts with 100 tokens. In the diagram below, they have a choice. If they are willing to lock up their tokens for two or three periods (say days, or months, or even years) they get 2x or 3x voting power from those tokens respectively.

You can of course engineer these ratios to whatever suits. If the discount rate—the number of voting bonds and therefore the voting power you get for longer commitments—is too high, everyone will just lock for the maximum period, reducing strategic decision-making. If it’s too low, it’s not attractive, so time commitment becomes irrelevant.

Our paper suggests an optimal discount rate balances the trade-off between voter influence and token liquidity. Since wealthier users often have better investment opportunities elsewhere, they are less likely to lock tokens long-term, allowing more engaged participants to gain influence. Bond voting has to be tested in real life scenarios and fine-tuned.

But the point of bond voting is to use opportunity cost (the foregone opportunity to use your tokens for something else) as a means of gathering information about preferences. The design solves the three problems above:

Plutocracy mitigation: Even wealthy participants must consider the opportunity cost of locking tokens for extended periods. It means that voters who are more passionate, or informed, or just more dedicated to the future of the community they are governing can get the information contained in their preferences to contribute towards the final decision.

It is sybil resistant: no voter can gain an advantage by splitting their tokens up or combining their tokens with others.

Better signal of preference intensity: Those who lock their tokens for longer tend to have deeper stakes in the project’s success. By locking up they signal greater confidence in the system’s long-term health. In fact, by locking up their tokens they are incentivised to care more about future choices.

There are, obviously, lots of variations you can construct of bond voting. One I’ve thought a lot about is that lockups could be cumulative - you could buy voting power for future votes by extending lockups.

The core insight of our paper is that time is an underutilized governance tool. One-person, one-vote, or one-share, one-vote is not the limit. If you have a machine that can enforce credible commitment, there’s a lot more you can do with human governance.

The backstory

This paper has a bit of a backstory. Sinclair Davidson, Jason Potts and I first scratched together a version of this in 2020 which we called commitment voting. We were working with some Australian crypto teams who were looking for innovative new ways to vote, and came up with that.3 It has parallels to other time-weighted voting systems like conviction voting, but is designed for discrete ballots rather than continuous approvals.

Vijay and Peyman (and to a lesser extent me) were able to formalise the intuitions of commitment voting, and realised that this was best understood (and priced as) a bond. At one stage I was trying to figure out how to use this mechanic to make fun video games:

After a lot of back-and-forth we managed to get it published at Management Science in early 2024.

There are already a number of blockchain projects interested in adopting some form of bond voting, and I hope that writing this up more accessibly can spread it further.

I recount this because there is an inside academic baseball point to make. Our belief when we set up the Blockchain Innovation Hub at RMIT University was that there are more interesting research questions emanating from outside the academy than within. So for seven years we were engaging directly with the crypto industry to learn about what was hard for them.

Too many academics approach private industry in the opposite way: they take their research and try to convince the rest of the world that it is applicable.

As we learned, it is much more productive, much more intellectually engaging, and much more fun to ask the world what matters first. Bond voting is one of the many results of that approach.

The rights to the token once it is unlocked can be traded, of course, and in fact the potential of secondary markets is a core part of any time-weighted voting system.

Our paper goes into some detail about quadratic voting, and Darcy Allen, Aaron Lane and I have an extensive discussion of quadratic voting in our book Cryptodemocracy.

We also came up with a much sillier and funnier idea at that time which I will share in due course.

Interesting to think about how this changes the equilibra in various public choice models of voting.