Back when I was working at the vast rightwing conspiracy I was given the task of revamping the IPA Review, which is now (I believe) the oldest continuously published political magazine in Australia.

Because we sold the magazine at news agencies I pretty quickly figured out that issues with pictures of people on the cover sold much better than those without. It’s a basic human thing. People like to look at pictures of people. We are attracted to other humans.

This, I think, is the key to work in an economy with abundant AI.

I’ve spent a bit over 20 years thinking of myself first and foremost as a typist writer. Twenty years was a good run. AI innovation has delivered a storm of existential shocks to the writing profession.

AI is spectacularly good at doing what we can now admit is the drudgery that takes up lots of intellectual and policy work. It can help get your head around complex issues quickly, without having to spend hours digging through website, after website, after report.

Of course you have to check the sources etc., etc., etc. Generative AI is now two and a bit years old and there are a lot of people still talking about the hallucination problem as a fundamental problem with AI. It absolutely was at first. But the models with deep research and search have come very close to eliminating hallucinations, at least for the sort of work I do. You might say that relying on the robot to do the background work is pretty risky, but to be honest it is much less risky than trusting your own stupid brain.

So the robot is a fantastic researcher and a perfectly adequate writer. But I don’t really use it to write. AI can’t seem to replicate what I think is my tone and voice. I’ve tried everything. I’ve fed every column I’ve written into the context window. I’ve had it analyse and build lengthy style guides to put in prompts. I’ve never been happy with the results. It’s not a skill issue, it’s a taste issue.

Ideally, I want my writing to sound like me. Like I’m talking. Like I’ve dictated the text directly (which, increasingly, I do).1 I don’t want it to sound human, I want it to sound like a specific human.

This is the comparative advantage we have over AI.

What remains of all the industries and occupations about to be disrupted will be the parts that connect people to other people. What matters in this world is personality, brand, emotion, connection, rapport, humor, identity, timing, respect, charisma, creativity, presence, integrity, leadership, storytelling, authenticity, charm, persuasion, vulnerability, openness, surprise, passion, tact and grace, diplomacy …

Israel Kirzner described the work of the entrepreneur as alertness: the ability to recognise opportunities that others overlook, even when not actively searching for opportunities. What will be prized in an AI world is relational alertness: the ability to identify the spaces in economic exchange where we can find human connection, to appeal to human values, to elevate our human qualities.

People like people.

Yes, this all is a bit woolly and earnest. Let’s recast the argument more formally. As I argued in the Soviet academia piece, production isn’t valuable, coordination is. Coordination is inherently social. It relies on the identification of wants in others.

The AI is great at producing interesting, or convincing, or compelling, or amusing work, but it doesn’t know when it has.2 Identifying human qualities is our job.

For other reasons I’ve been reading Friedrich Hayek’s The Sensory Order, the great economist’s surprising diversion into neuropsychology which he published in 1954.

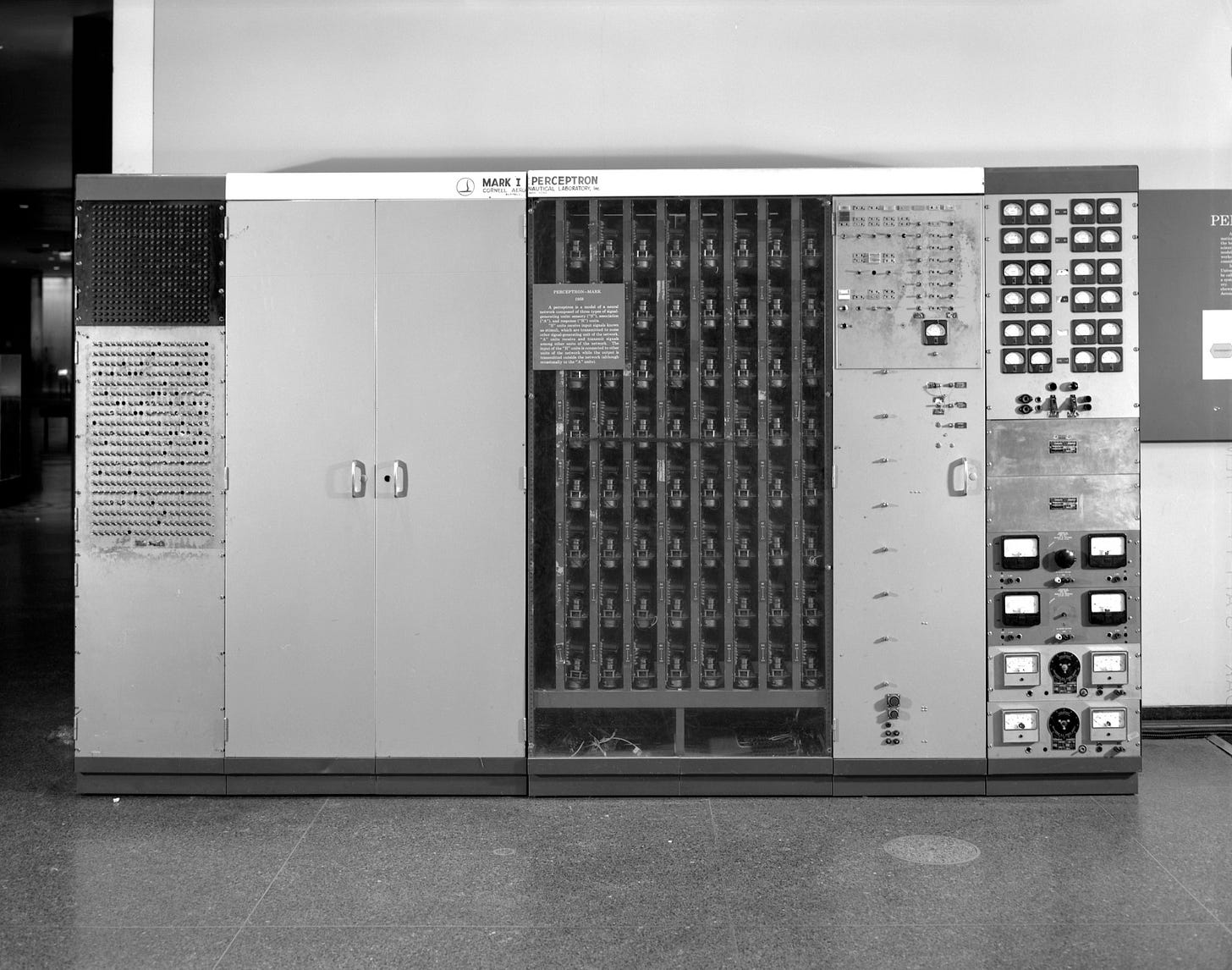

The Sensory Order is undergoing a bit of a revival because the ideas that Hayek explores in there are some of the foundation ideas of neural networks. Frank Rosenblatt, who created the first neural network (the 1957 ‘Perceptron’) cited Hayek among others as establishing the theoretical basis of his device.

Hayek’s idea in that book is that our subjective preferences are created from the unique arrangement of neural connections in the brain. That arrangement is determined by particular sensory interactions we have had in the world, from the most basic (taste, touch and all of those) to the higher order abstract ideas we learn from others (culture, value and all of those).

Hayek’s idea of the brain is mechanistic. It doesn’t have anything ephemeral like a soul. In principle, it is a machine where if you run the same input twice you’ll get the exact same output. But everybody’s neural map is different because they have experienced and learned from a stock of different sensations. The human diversity of wants and preferences are created by those differences. We are all built different because we learned different.

We now have an economy divided into two types of neural networks, each interacting with the other. There are those neural networks who have learned from a lifetime of sensory inputs - we call them humans. And there are those which have learned from the mass product of human endeavour - the large language models trained on the entire corpus of the internet. The intelligence latent in each type of neural network is overlapping but not complete.

In a world of robots, our job is to address our work and effort to what is distinctly human about those neural map. To predict the desires of brains built different to ours.

This post is titled “AI makes us more human” but it is really that AI forces us to be more human. We have to focus our attention on the areas where AI neural competency does not overlap with human neural competency.

AI is more replacement than complement

This is why I think a lot of people are getting confused when they talk about how AI will be a “complement” to human labour.

We hear that a lot in education. Now, it is strictly correct. I don’t see any reason that AI could make employers step off the credential-inflation treadmill. We’re still going to need some organisation to provide credentials. Let’s call them universities, and the staff that gatekeep those credentials educators.

But too often the complement argument is just cope. I often hear it more as a plea than a prediction: “of course it is vital that we keep having teachers”. Vital for who? The students or the teachers?

I am sorry but it is more realistic to think of AI as a replacement in education than a complement.

University educators will be doing radically different things than they do today. Indeed, those educators might not be the same people as they are now. It might not make sense to call them educators: maybe more advisors, concierges, intermediaries (between what employers demand and what graduates can supply), and disciplinarians.

Many of the core functions of the modern lecturer (information provision, learning facilitation, curriculum and content production, customer service) are more efficiently, and already sometimes better done by AI.

If we are to say that AI is a complement, we must admit that it will be complementing radically reconfigured roles.

AI is even more effective at the sort of personalized support to help students navigate content that is the gold standard of education practice.

We’ve all had mentors in our life, and we’ve all had the same experience. The mentor talks us through how to do something or how to think about something. We ask some questions.

But we don’t ask all the questions we have. We don’t want to embarrass ourselves in front of our mentor, lest they think us unworthy of their effort. So we hold back. We let critical materials or ideas slip past.

Try using an AI for intellectual mentoring. The robot doesn’t judge. You can ask it anything, with no consequence. In fact (I find) the stupider the question the better the result.

It doesn’t judge because it is not a human. Embarrassment is an emotion we experience in the process of interacting with other people. We often value the respect of other people more than we do the knowledge they could pass to us.

This is an example where human nature actually limits value creation, and thus a great opportunity for AI to replace human effort.

Our job in the AI economy is to find out how to exploit our most human qualities to create value for others.

I’ve been using Speechpulse recently. It’s pretty cool.

This is why AI labs spend so much on reinforcement learning through human feedback. They have to try to brute force human judgement into the models.

Very good essay on much the same theme: https://fakepixels.substack.com/p/jevons-paradox-a-personal-perspective